Healthy Living Centres as a Way to Promote Sustainable Communities

By Mark Lam

(Student work. Presented at the University of Melbourne - Environmental Design)

The term Market Society in this discussion refers to a capitalist market economy that influences the exchange of goods and services in a society as well as the personal attitudes, lifestyles and political views of its people.

The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED; Brundtland, 1984) definition of sustainability states:

Sustainability is development that meets the needs of humans and other living beings of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.(1)

The core concept of a sustainable environment is that there should be clean air, fresh water, sunlight (an effective ozone layer), fertile land and an abundant diversity of species. Furthermore it should address issues regarding habitat, society, economy, politics and culture. Hence, sustainable development means the development of all the above factors in a sensitive and sensible manner for the present as well as future generations.

Social sustainability is the harmonious co-existence of people within their society and environment (2). Arnie Næss, the author of the Deep Ecology philosophy states, “The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.” (3) A socially sustainable society does not have to be rich in terms of materialistic wealth, but has to be rich in terms of social and cultural wealth, which can be used for current and future generations.

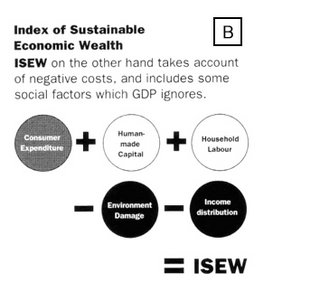

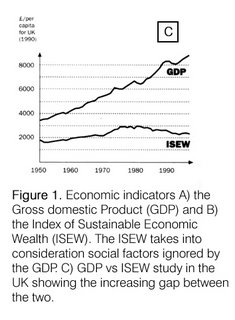

The Market Society’s negative effect on social sustainability in cities is described by Sir Richard Rogers: “Cities are destined to house a larger and larger proportion of the world’s poor. It should become no surprise that societies and cities that lack the basic equity suffer intense social deprivation and create greater environmental damage – environmental and social issues are interlocked” (4). Most economists gauge the prosperity of a country using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which takes into account consumer expenditure, social costs e.g. welfare and environmental cleanup costs. The GDP however, is not a clear indication of the quality of life. The World Bank conducted a survey of OECD counties and found that in countries that had its economies owned by the richest 20 percent of its population, there was a lower rate of long-term growth (5,6). A better indication of the quality of life in country is the Index of Sustainable Economic Wealth (ISEW) takes into account all other social factors (not just economic costs) which are ignored by the GDP (Figure 1 explains this concept in graphic form).

In Australia, the divide between the rich and the poor is expanding and families that fall in the mid-range income bracket are declining. (8) Indicators for this inequality include rising unemployment rates and the increase of part-time and casual jobs in the country (see Figure 2). Richard Sennett discusses some of the undesirable consequences of increasing part-time and casual employment in more detail (9). Low-income individuals are often caught in a cycle of entrenched disadvantage, as they experience a lack of power, have limited opportunities for social participation, suffer from a lack of education/or skill levels and low self-esteem. The market society’s manifestations of globalisation, post-industrialism and e-commerce have the potential to exaggerate the situation for the poor. Furthermore, differences between the rich and the poor are manifested spatially where poorer people are relegated to certain suburbs, in housing commission flats or social housing. It is important to avoid social exclusion by having urban and regional policies that provide initiatives addressing such problems so that a balanced society within a stable economy can exist. (10)

Wealth, Health and the Community

The classic symptoms of poverty include poor education, poor environment and poor health, high crime rates, unemployment, drug abuse and social isolation. These demonstrate that economic and social systems are intertwined (12).

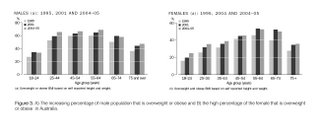

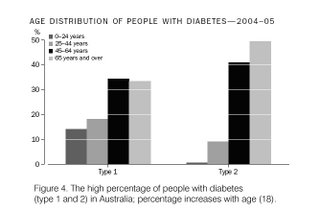

“More than 90% of people walking about in an ordinary neighbourhood are unhealthy, judged by simple biological criteria. This ill health cannot be cured by hospitals or medicine.” (13) This statement was made in 1977 based on observations of people in the United States of America. Thirty-one years later, the situation has not changed much. Based on the 2005 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) report on Body Mass Index (BMI), 62% of males and 45% of females are classified as obese or overweight (Figure 3A and B). Diabetes is another indicator of physical health and the incidence of people suffering from this (mostly) diet related disease is high (Figure 4). Patients with diabetes are also highly susceptible to heart and vascular diseases. In terms of mental well-being, 57% suffer from depression or mood disruptive disorders, and 55% suffer from anxiety related disorders (14). Other diseases that can be prevented by improving diets, lifestyle and environments include cancer (15) and allergies (e.g. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, MCS) (16).

The condition of our environment directly affects our health and well-being. Humans are by instinct sociable, hence a sustainable environment also means that there should be provision for human interaction and strong community support.

A proposal for Healthy Living Centres

The poor are often less healthy than the rich (19). An effective way to minimise this discrepancy would be to provide a place for poorer communities to be exposed to the concepts of health, enterprise, learning, environment and the arts. Healthy Living Centres are places for people to improve their physical, emotional and spiritual health. By addressing the issue of socially sustainable societies, current and future generations stand to benefit from its effects as these interventions will impact on the care given to the environment and in the long-term, sustainability of the economy.

Some examples of Healthy Living Centres.

Healthy Living Centres for the community already exist. Described below are a few examples of how these centres operate.

The Peckham Health Centre (The Peckham Experiment).

The Peckham Health Centre (20,21) was set up in 1935 by two doctors George Williamson and Innes Pierce who were interested in preventative social medicine for the working class. Their aim was to study the effect of environment on health in a deprived working class area. 950 families paid one shilling a week to use the club-like facilities, engaging in physical exercises, games, workshops or just relaxation. There were no set exercise programmes, and members were obliged to attend a thorough medical examination annually.

Sir William Owen designed the building in the modern style. The heart of the centre was a large swimming pool with a glazed roof. It had long stretches of windows that allowed plenty of natural light and fresh air in. Cork floor surfaces allowed children to wander around barefoot. All parts of the building were used including the roof, which was used for exercise classes. The interiors were simple, with floors supported on cruciform columns with the minimum number of internal walls, providing for a flexible space. It also provided for spontaneous social interaction in a community setting and for doctors to observe the members at play. There were no hidden, dark treatment rooms.

The centre closed in 1950 due to funding problems and because its philosophies did not fit into the National Health Service (NHS) at the time. The project became Pioneer Health Centre Ltd., and its philosophies have now been embraced by the UK government in the form of the Healthy Living Centres Initiative (22), which is well funded by the Lotteries. The architectural design of this building was purely for functional outcomes, unlike the next example, the Finsbury Health Centre.

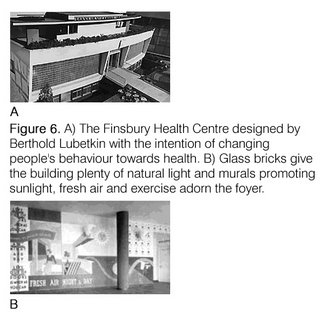

The Finsbury Health Centre, UK.

The Finsbury Health Centre (Figure 6) is located in one of the poorest boroughs in London. As part of the Finsbury plan, the Finsbury Health Centre, designed by Berthold Lubetkin (23) (and Tecton) was opened in 1937 (24). The Finsbury Health Centre provided the opportunity for Lubetkin to use architecture as a catalyst to change people’s behaviour. The design of the centre provided plenty of natural light (using glass bricks) and ventilation. The centre had a brightly coloured scheme and cheerful murals promoting sunlight, fresh air and exercise as a way of life. The waiting rooms were arranged to provide a club-like atmosphere rather than the traditional rows of seats. Planning was flexible to cater for the ever-changing needs of the clinicians.

The services provided in the Finsbury Health Centre were of the curative approach, which also included a TB clinic, a foot clinic, a dental surgery, and a solarium, in line with the policies of the NHS at the time. The health center provided the first example of the marriage of modernist architecture with a strong social reforming agenda.

The Sacred Heart Mission, St. Kilda, Victoria Australia. (25)

The Sacred Heart Mission Centre (Figure 7) caters specifically for the poor living in St. Kilda and neighbouring suburbs. The centre has two healthcare facilities, one for a GP and another for allied health services. All services are provided on a gold coin donation basis or free if the client cannot afford it. Other programs include a soup kitchen, laundry, showers, accommodation for the homeless aged & women. Funding is obtained from government sources, charities and activities of its own opportunity shop. Full-time staff and volunteers run the facility. Administration and the GP’s clinic are located in the converted vestry, the soup kitchen café and opportunity shop are located in the converted Church Hall and the health centre and hostels are located in a converted primary school. Surrounding houses are also incorporated into the hostel complex.

The reuse of buildings is well planned for their functions. The opportunity shop, cafe and soup kitchen as well as the grounds surrounding the buildings have plenty of sunlit sitting areas conducive to social interaction. The main feature that is lacking in the whole scheme are areas for exercise or physical recreation, like those provided for the Peckham Centre, hence depriving facility users of closer social interaction. Staff at the centre organise sports programs, making use of surrounding sporting facilities, but the effect is not the same. The architecture or the buildings are reflective of the history and the main function of the site, as a Church. The Church has adapted its stock of buildings well to serve an urgent community need, showing an appropriate response to encourage social sustainability.

Borondarra Community Health Centre, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia.

The Borondarra Community Health Centre (Figure 8A) provides a large range of healthcare services to residents in the Borondarra council (26). A wide range of health and counselling services are provided. Patients are either bulk billed, or charged a consult fee according to services provided. As the size of the building is limited, there is only a small general-purpose room which can also be used for exercise activities such as yoga or pilates. The centre is one of a network of three centres, run by a not-for-profit-organisation (27), with funding through the National Health Scheme (NHS) and government grants. Workers are paid full salaries, with no volunteer workers.

Located in the old post office building, next to the town hall, and close to the train station, its central location makes it clearly visible and easily accessible. The recycling of the old post office is an environmentally friendly option. However, the consult rooms were split into traditional arrangements of little rooms of central corridors, and sometimes were not as well lit by natural light and there was a larger reliance on mechanical ventilation (Figure 8B). The arrangement of the waiting area, with its traditional rows of seating also make it feel much like the average waiting area in hospitals and clinics. The centre, although run as a not-for–profit organisation is administered very much like a business and the ideas of compassion and charity for the community, are less evident.

The ideal situation: an interconnected network of Healthy Living Centres.

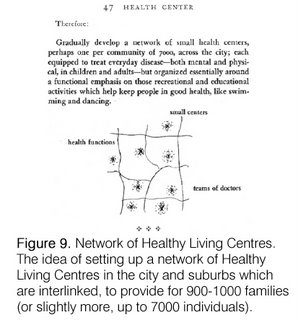

Studies have shown that some mass media promotions about improving health are only partially effective (28). Another way of promoting healthy living is to create a network of Healthy Living Centres within the city, each catering for about 7000 people that provide overlapping facilities so that these can be shared between centres (29). The overlap of facilities also means people from poorer suburbs can interact with those from wealthier areas. The aim of creating a network of such centres is to promote within and between communities the culture of exercise, social or community activities, education about personal health and lifestyle habits, and to provide healthcare services. The establishment of these centres is not only a form of preventative medicine, but a tool to educate the population on lifestyle habits, which have positive effects on environment sustainability and the economy.

The kind of services provided for each centre should be specific to the requirements of the community. Factors like socio-economic differences, environmental and cultural differences need to be catered for. Some of these migrants arrive as refugees, and in most cases are poorer and have language barriers. The cultural issue of healthcare then, has to be taken into consideration. For example, among the Vietnamese, the symptoms of depression are felt in the body rather than the mind (i.e. somatisation of their depression). Their treatment would be massage rather than counselling, as is the norm for Anglo-Australians. (31) The old biocentric model of “man” (32) which is commonly used in western societies has to be made redundant, as the population becomes more and more diverse.

The ability to adapt to changes in population demographics is important. For example, provision will have to be made for an ageing population. The design of buildings should be flexible, and must take into consideration these changes (33).

Philosophical views of health, illness and well-being are always evolving (34) and the society (35) and political agendas have strong roles in influencing these (36,37). Perception by the community of the type of health-care (e.g. Allopathic, Holistic, Chinese Medicine etc.) that works is also important (38). The careful selection of services based on its effectiveness for each community is therefore crucial. These choices should be done without financial and political influences (39).

The environment in which we live in is important to our health. There are many man-made agents (such as chemicals and radiation) that can be harmful to our health. Initial exposure to these may not have any effect on our health and well-being, but in the long term can be dangerous. Saunders, in his book the “The Boiled Syndrome” explores this topic in great detail (40). The importance of location, material selection and sustainable design can be infused into the thinking of communities through the Healthy Living Centres; hence, the architecture of the centres becomes important in promoting sustainability ideas.

The aesthetics of the healthy building is expressed well by modernist architecture. Some modern architects have specifically designed their buildings with the aim of promoting health. Aalvar Alto’s Paimio Sanitarium (Figure 10), was designed specifically for tuberculosis patients, who needed plenty of sunlight and fresh air to recover. Alto designed to the smallest details, including the fittings and furniture, to aid in the patients feeling of well-being. Berthold Lubetkin’s Finsbury Health Centre is another example, which was discussed above. Architectural styles are constantly evolving, and like healthcare methods, whichever style that suits the function of providing a feeling of sustainability for that community, it should be adopted. The recycling of buildings is a good idea in terms of environmentally friendly construction practices; however, some of the limitations of older buildings (especially ones with less access to natural lighting) may hinder the promotion of feeling of healthiness. Buildings that are designed specifically for this function and which have flexible floor plans would be ideal for the use as healthy living centres.

Factors for and Against the Establishment of Healthy Living Centres

Some factors that make the idea less attractive to decision makers are that the initial outlay for setting up a network of such centres may be high, their effects are not immediate and are difficult to measure (41). As most governments make decisions based on the popularity of the decision and the voting public (which usually excludes the poor and the young) have ignored the issues of health and community, as a means of promoting a sustainable society, decisions to fund such places are hard to justify. Being sick is also good for business (42), and this means that market forces actually support the idea of being sick. Other issues relating to difficulties in setting up such centres are the staffing of such places, i.e. working in places with less prestige or lower pay, having to deal with social ‘undesirables’, the expected difficulties working with the ill informed and changing their mindsets. With most establishments dealing with the public, administrative ‘red-tape’, legal and insurance issues will increase operational costs and hinder good initiatives.

For Healthy Living Centres to be set up and maintained, there needs to be strong policies and funding. Some ways of getting the ideas across to influence decision makers about the benefits of such centres include:

- Setting up lobby groups to promote the idea to local, state and federal leaders. Infusing ideas into Local Councils and planners so that their Urban Design Strategies (43) include planning for such facilities. It is important that government bodies provide initiatives to establish such centres.

- Educate the mass population about the concept as a means to gain voter support. Starting up debates using the mass media (e.g. newspapers, television and radio programmes) are a good way to expose the concept to the public.

- Starting up prototypical centres to show that it works. Funding may have to come initially from charitable sources until government support can be obtained. The Sacred Heart Mission is a successful local example of the concept.

Concluding Comments

The idea of setting up Community Health Centres is an attempt to improve the health and well being of the community both physically and mentally. For these centres to be effective, communities of lower social-economic standing in cities should be targeted (45). These centres create greater social equity. Downstream effects of this holistic approach include more sustainable environmental and economical development, and the negating of undesirable effects currently created by the market society (Figure 11). In order for this to work, governing bodies must play an active role in the promotion of such centres.

Endnotes

1. UN General Assembly document A/42/427. Our Common Future. Oxford University Press. 1987

2. Sennett, R. Capitalism and the City.

3. Næss, Arne. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. 1989.

4. Rogers, R. and Gumuchdjian, P. 1997. p. 7.

5. Planning Institute of Australia. 2004.

6. Stekekee (1999)

7. Rogers, R. and Gumuchdjian, 1997. p. 154.

8. Yates and Wulf, 1999 and Lloyd, Harding et al. 2000.

9. Sennett, Richard. 2001.

10. Planning Institute of Australia. 2004.

11. Sheehan, P. and Gregory, R. 1998.

12. Burdess, N. 1999. pp 149-171.

13. Alexander, C. et al. 1977. p. 252.

14. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey, 2004-2005. 27 Feb, 2006.

15. Zaza, Briss and Harris. 2005. p143

16.www.housesforhealth.org.au. Website set up by Australian architects running a not-for-profit organization to address housing and environmental issues for people suffering from Multiple Chemical Sensitvities (MCS).

17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey, 2004-2005. 27 Feb, 2006.

18. Ibid.

19. Burdess, N. 1999. pp 149-171.

20. Hall, L. http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTD004752.html

21. http://www.open2.net/modernity/3_6.htm

22. http://www.caerphilly.gov.uk/healthyliving/healthyliving.htm

23. Allan, J. 2002.

24. http://www.open2.net/modernity/3_5.htm

25. I would like to acknowledge Mr. Vince Corbett for showing me the facilities.

26. I would like to acknowledge Beng Lee Foo, RN for showing me the facilities.

27. http://www.iechs.com.au/

28. Zaza, S., Bris, P.A. and Harris K.W. (eds). 2005.

29. Alexander, C. et al., 1977. p. 252

30. Alexander, C. et al., 1977. p. 252

31. Julian, R. and Easthope, G. 1999. p95-114.

32. Lock, M and Gordon, D. 1988.

33. Means R., Richards, S and Smith, R. 2003. Issues regarding aged care are discussed in detail in this book.

34. Grbich, C. 1999. pp 3-13.

35. Collyer, F. 1999. pp 217-237.

36. Griggs, B. 1997.

37. Wearing, M. 1999. pp. 197-216.

38. Lam, T.P., 2001, pp.762-765.

39. Wearing, M. 1999. op.cit.

40. Saunders, T., 2002.

41. Zaza, S., Briss, P., and Harris, K. pp. 80-113.

42. Pallisco, 2006.

43. So that these proposals can be published and made into public documents such as the Knox Central Urban Design Framework, 2005.

44. Rogers, R. and Gumuchdjian. 1997. p149.

45. Rogers, R. and Gumuchdjian, P. 1997. p1-23.

Bibliography

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M. with Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I and Angel, S. A Pattern Language. Towns. Buildings. Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Allan, J. Berthold Lubetkin. London: Merrel, 2002.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey, 2004-2005. 27 Feb, 2006. Retrieved May 1, 2006, from http://www.abs.gov.au/.

Burdess, N. ‘Class and Health’ in Grbich, C. (editor). Health in Australia, Sociological Concepts and Issues. 2nd Edition. Australia: Prentice Hall, Longman. 1999. pp 149-171.

Collyer, F. ‘The Social Production of Medical Technology’ in Grbich, C. (editor). Health in Australia, Sociological Concepts and Issues. 2nd Edition. Australia: Prentice Hall, Longman. 1999. pp 217-237.

The Finsbury Health Centre. Retrieved April 30, 2006, from http://www.open2.net/modernity/3_5.htm

Grbich, C. ‘Approaches to Health’. in Grbich, C. (editor). Health in Australia, Sociological Concepts and Issues. 2nd Edition. Australia: Prentice Hall, Longman. 1999. pp 3-13.

Griggs, B. New Green Pharmacy. London: Vermillion, 1997.

Hall, L. Positively Healthy. Retrieved May 1, 2006, from http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTD004752.html

Healthy Living Centers Initiative. Retrieved May 2, 2006, from Houses for Health, Australia. Retrieved May 20, 2006. www.housesforhealth.org.au.

Inner East Community Health Service. Retrieved May 14, 2006, from http://www.iechs.com.au

Julian, R. and Easthope, G. ‘Migrant Health’ in Grbich, C. (editor). Health in Australia, Sociological Concepts and Issues. 2nd Edition. Australia: Prentice Hall, Longman. 1999. pp. 95-114.

The Knox Central Urban Design Framework. 2005. Retrieved April 3, 2006, from http://www.knox.vic.gov.au/upload/Part1KCUDF.pdf

Lam, T.P., ‘Strengths and weaknesses of traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine in the eyes of some Hong Kong Chinese’. J Epidemiol Community Health, 55, 2001, pp.762-765.

Lock, M and Gordon, D. Biomedicine Examined. Kluwer Academic, 1988.

Means R., Richards, S and Smith, R. Community Care: Policy and Practice. 3rd Edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Næss, Arne. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 1989.

Pallisco, 2006. Michael Pallisco, ‘Sick generate healthy demand’, The Age Wednesday 17 May 2006, Business p. 7.

The Peckham Centre. Retrieved April 30, 2006, from http://www.open2.net/modernity/3_6.htm.

Planning Institute of Australia. Liveable Communities. How the Commonwealth Can Foster Sustainable Cities and Regions. February 2004. Retrieved May 1, 2006, from http://www.planning.org.au/vic/images/stories/health/drafthealthpolicy.pdf

Rogers, R. and Gumuchdjian, P. Cities for a small planet. London: Faber & and Faber, 1997.

Saunders, T. “The Boiled Frog Syndrome, Your health and the built environment”. West Sussex, England: Wiley Academy, 2002.

Sennett, R. Capitalism and the City. 2001. Retrieved April 30, 2006, from http://on1.zkm.de/zkm/stories/storyReader$1513

Sennett, Richard. New Capitalism, New Isolation: A Flexible City of Strangers. Le Monde Diplomatique. 2001. Retrieved May 1, 2006, from http://mondediplo.com/2001/02/16cities.

Sheehan, P. and Gregory, R. ‘Poverty and the Collapse of Full Employment’, in R. Fincher and J. Niewenhuysen (eds), Australian Poverty: Then and Now. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1998.

Planning Institute of Australia. Liveable Communities. How the Commonwealth can foster sustainable cities and regions. Feburary 2004.

UN General Assembly document A/42/427. Our Common Future. Oxford University Press. 1987

Wearing, M. ‘Medical Dominance and the Division of Labour in the Health Professions’ in Grbich, C. (editor). Health in Australia, Sociological Concepts and Issues. 2nd Edition. Australia: Prentice Hall, Longman. 1999. pp. 197-216.

Zaza, S., Bris, P.A. and Harris K.W. (eds). The Guide to Community Preventative Services. What Works to Promote Health? New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please select a profile under "comment as". If you don't have a profile, sign as "anonymous" making sure you write your name in the body of your comment.