Climate Refugees: Global Responsibility in a Market Society

By Sarah Bridges, architecture student, Melbourne University, 2006

By Sarah Bridges, architecture student, Melbourne University, 2006

Subject: Environmental Design - Market Economy and Market Society

Subject coordinator: Dr Darko Radovic

Studio leader: Beatriz C. Maturana

1.0 INTRODUCTION

“By recognising environmental refugees you recognise the problem. By recognising the problem you start on the road to accepting responsibility and implementing solutions”(1)

(Jean Lambert, Greens MEP 2002)

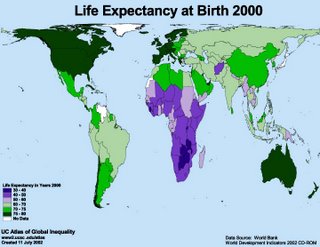

The following essay attempts to not only continue, but provoke discussion on global responsibilities in terms of sustainable development in a market society. The plight of climate refugees from around the world is exemplary of a history of neglect in the global civil society. This neglect has compounded from economic, social and environmental inequalities, which has resulted in unstable futures for a predicted 150 million people by the year 2050 (2). This situation was caused due to problems not only in political and legislative arenas, but also in the inherent understanding of the individual and the greater mass about what part they play in the “sustainable world”. Andrew Simms, co-author of, “Environmental Refugees – The case for recognition”, 2003, comments that “we face a ‘homes-for-lifestyles’ scandal, in which people in poor, vulnerable countries pay with their homes for the lifestyles of the rich”. It is therefore only by changing neo-liberal or industrialized human nature, through implementation of political and legislative decisions in favour of repairing the situation, that a solution can be found. Thus the rich and poor can still live with equal access to the worlds basic resources, such as clean air, water, and most importantly solid ground to build their lives, families, communities and cultural identities on. See Fig 1.

2.0 GLOBAL INEQUALITIES

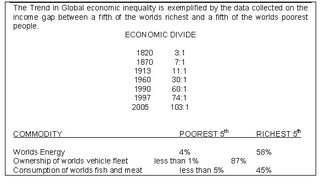

According to the United Nation Development Program (UNDP) Human development report 2005, although poverty has been reduced in some parts of the world, 25% of the world’s population is still stuck in severe poverty, and the gap between rich and poor is continually widening.(3) (See Fig. 2) When the world’s global economy is currently trading over $25 trillion, this begs the question of why are there still shameful inequalities and where are the national and international policies to prevent the economic, social and environmental inequalities, which are leading to unstable futures for over a quarter of the world’s population?

2.1 Economic Inequalities - Globalisation

Globalisation has been the major factor most analysts use as reasoning for the divide. It is therefore important to get an understanding of this term when discussing global economic inequalities. Sociologist Sasskia , from the

Neo-liberalism - Value is equal to price

- Value of species to be saved from extinction by what must be paid for their protection

- Does not recognize limits to market forces, but only to the efficacy of government action.(6)

Market Society- The value of everything is measured by what people are prepared, or able to pay for it.(7)

It seems therefore that perhaps the solutions lie therein, that being a champion of globalisation (i.e., successful international organisation) and turning a blind eye to global equity concerns should be the target of legislative moves. This is supported by

These economic inequalities are the catalyst for the butterfly effect on many detrimental problems within the world today. They lead to social and environmental inequalities which is where the real material and psychological detriment is felt.

Social Inequalities – Diminished Quality of Life and Life expectancy

Plato wrote in the fifth century BC warning Athenian lawmakers of the threat posed by extreme inequality. “There should exist among the citizens neither extreme poverty nor again excessive wealth, for both are productive of great evil.”(9)

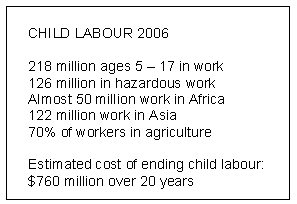

Interestingly, the hero of neo-liberalism Adam Smith, agreed, stating, “No society can be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of members are poor and miserable. Relative poverty is a where all members of society should have an income sufficient to enable them to appear in public ‘without shame’ ” (10). These statements are important in defining why social inequality is a major issue to be faced and how although social inequalities have been faced for centuries they should not be simply accepted. A blind eye has often been turned by the global civil society and thus continuation of the poverty cycle for many has persisted. See Fig 3. Statistics show that this has meant not only an economic gap but also a social gap, both playing the game of the chicken and the egg…which one came first?

2.3 Environmental Inequalities – Future Instability

“Ironically, those least responsible for Global warming or poorer nations are generally more vulnerable to the consequences of global warming. These nations tend to be more dependent on climate-sensitive sectors, such as subsistence agriculture, and lack the resources to buffer themselves against the changes that global warming may bring. “(11)

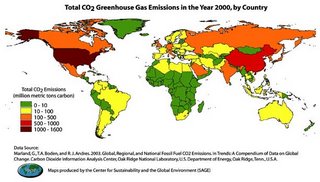

Global warming emissions of a country in comparison to its average life expectancy are direct indicators of Environmental stability in a country. Countries such as Australia having the highest per capita CO2 emissions at 1.4% of the worlds emissions, have a longer life expectancy, lower poverty gap and better future living opportunities in comparison with all the nations of the pacific islands, creating 23 times less emissions than Australia at 0.06% (12). Yet, it is these nations who will pay the highest price, if something isn’t done to curb our energy hungry and responsibility shy nation.

Whilst it is argued that through the economic divide, environmental inequalities have resulted, perhaps it should be looked at form another angle where the result has driven the cause. Andrew Simms’ book, “Ecological Debt – the health of the planet and the wealth of nations”, describes the paradox of how the global wealth gap was built on ecological debts, which the world’s poorest are now having to pay for. He suggests that the developed nations have exported their skill to less developed countries as economic immigrants, to find wealth and prosperity in an under legislated environment. They have taken advantage of lower laws on environmental protection and directly exported the financial gain back to the developed countries. All at the same time as strengthening the border controls of who is able to enter in their own more developed lands, as perhaps unskilled immigrants also looking for economic opportunity. Thus, the only benefit seen by the indigenous owners in less developed countries is a rise in production and export in the face of their own ecological demise. He goes on to describe the possibility of an “ecological debt”.

“Imagine opening a bank letter at breakfast to find that instead of your normal overdraft, you had an ecological debt that threatened the planet. If the whole world wanted to live like people in the

This brings us to the case of Climate Refugees from around the world. People from less developed nations, who are directly affected by the detriment the environment has taken, and are still waiting for responsibility to be taken and the ecological debt to be paid by those from more developed countries owing.

3.0 Climate Refugees – Recognition and Responsibility

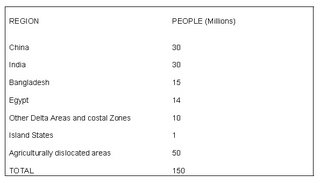

Climate Refugees are “Inhabitants from countries where the impacts of Climate Change, which include increased droughts, desertification, and sea level rise, along with more frequent occurrence of extreme weather events, inhibit their future social, economic and political survival.”(14) Factors such as; Food security, Water security, Increase in Vector and water borne diseases, Infrastructure and Land losses and Sea Level Rise are all too quickly arising in many less developed or environmentally unfortunate countries. Recent estimates suggest, “25 million people worldwide were uprooted for environmental reasons – compared to 22 million displaced by civil wars and persecution” (15). Another estimate suggests that by the year 2050, there could be 150 million climate refugees needing to be displaced. (16) See Fig 4.

Environmental refugees are currently not officially recognised and protected by the international community in a world of growing interdependency – where environmental problems have no respect for borders and nation states. The paranoia of wealthy countries is deeply ironic. Their carbon intensive lifestyles are driving global warming, which is likely to become the largest single factor forcing people to flee their homes around the world. There is an obligation on the nation’s most responsible for historic greenhouse gas emissions, to make sure that environmental refugees are recognised and protected. However, the Geneva Convention on Refugees contains no explicit clause to acknowledge their plight. Without a planned approach to managing the environmental refugee crisis, there will be chaos, avoidable suffering and a backlash against innocent victims of global environmental degradation.

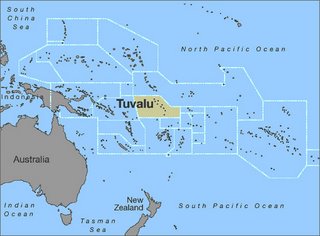

This problem has already been faced in

4.0 Case Study –

The appeal by the Tuvaluan government in 2000 was shamefully denied by Australia’s Phillip Ruddock, the Immigration Minister at the time, who stated that accepting environmental refugees from Tuvalu would be “discriminatory”.(17) Fortunately, New Zealand, a country of lesser size, and lower economic stability, put its hand up to help. Setting an example for the rest of the world, unfortunately however, unmoving to its closest neighbour. In March 2002, Prime Minister Koloa Talake announced that he was considering legal action against the world’s worst polluters, the nations most responsible for carbon dioxide emissions at the International Court of Justice.(18) And today in 2006, there is still yet to be discussion on a new immigration category within Australia. This example shows the urgency of diplomatic action needed to accommodate for the bleak future of climate refugees. It is merely a taste of the “Chaos” which many writing on Climate Refugees predict if the global civil society does not own up to its environmental responsibilities.

5.0 Global Responsibility

Andrew Bartlett of the Australian Democrats suggested in 2002 that if

There is further need for a logical discussion to take place on global responsibility in the future. The ratio of emissions to immigration is one particular category dealing with climate refugees which is in effect only a short term answer to a long term problem. World leaders need to combine efforts, and put the issue on the table. There has already been response from some of the most powerful in regard to the effects climate has on immigration patterns from Tony Blair and Bill Clinton (see Fig. 7). However, it is obvious, that in today’s “market Society” there is greater need for legislation and policy making. While the immediate problem about to be faced by 150 million people needs an answer, perhaps more urgent is the answer to how we treat our global environment, and when we are going to stop abusing it. This was best put by the Tuvaluan Governor-General Sir Tomasi Puapua, at the 57th session of the UN General Assembly in September 2002,

“Taking us as environmental refugees, is not what

5.0 Solutions

When it comes to a solution to the problem it is not just a matter of small change. In a market society value is driven by price, and how much people are prepared to pay for something with money. Instead, the emphasis should be on whether the environment is able to pay for something. Perhaps it may take what Lester Brown describes as ‘launching the environmental revolution’ for any changes to fully assist in the possibility of a sustainable future.

“There is no precedent for the change in prospect. Building an environmentally sustainable future depends on restructuring the global economy, major shifts in human reproductive behaviour, and dramatic changes in values and lifestyles. Doing all this quickly adds up to a revolution, one defined by the need to restore and preserve the earth’s environmental systems. If this environmental revolution succeeds, it will rank with the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions as one of the great economic and social transformations in human history” (20)

The following are a number of solutions put forth for dealing with the issues of Climate Refugees:

- Discussion on a political level regarding plight of Climate refugees

- Opening of a new category of Immigration by the immigration department directly related to climate disadvantage. (Australia has a disproportionate responsibility for creating them, and hence an onus to officially recognise them as a separate category of refugee.) (21)

- Recognition of responsibility directly regarding emissions affecting other countries.

- Payment of ecological debt to those owing through political discussion

- Assessment of causes behind climate Refugees, and collection of data, to make the problem a reality in the political arena

- Education to the public about the plight of Climate Refugees

- Increase the Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) from Australia to the United Nations target agreed upon in 1970, to 0.7% of the Gross National Income (GNI). Australia currently gives 0.41% (22)

Recommendations in Simms’s book for dealing with ecological debt include: (21)

1. Legal recognition and protection under international law for environmental refugees displaced by climate change and environmental degradation.

2. Rich countries to pay the cost of the rest of the world having to adapt to global warming.

3. Trade sanctions to be used against non-Kyoto states such as the United States and Australia

4. Cancellation of the unplayable conventional debts of poor countries in the face of rich countries' ecological debts

5. Gas guzzling urban 4x4 cars to carry environmental health warnings like cigarette packets.

6. The end of government subsidies to fossil fuels

7. In the light of global warming, a G8 reassessment of the resources necessary to meet the international poverty reduction targets of the Millennium Development Goals

8. A global framework to follow the current Kyoto Protocol based on the principle of equal, per person greenhouse gas emissions entitlements and cutting emissions to a level to stop dangerous climate change (known as contraction and convergence)

9. Compulsory therapy for key decision makers to help them deal with their denial about the scale of action necessary to deal with climate change.

10. A new model of economic development in which the acid test will be whether any policy increases or decreases human vulnerability to climate change.

6.0 DEFINITION AND POSITION OF TERMS

in terms of sustainable development:

“ of industrial society includes not only the of factories, but the of pollution, of weapons production, of western technocratic management and its communications infrastructure”. (24)

Global Responsibility:

“By recognizing the problem you start on the road to accepting responsibility and implementing solutions” (25)

Sustainable Development:

A holistic approach to the process of development. Encompassing issues to do with environment, society, economy, politics and culture, both today and in the future

“Use of an area within its capacity to sustain its cultural or natural significance, and ensure that the benefits of the use to present generations do not diminish the potential to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations. Use of and visits to areas must contribute to social and economic well-being of the nations and its constituents without detriment to the heritage resources; and the integrity of the heritage resources is never jeopardized” (26)

Market Society:

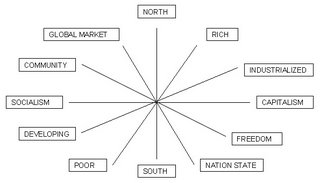

When first unravelling the term of ‘market society’ it is difficult to ignore the underlying fact that these are two contradictory terms. “Market” has roots in economic benefit and competition, whilst society has deeper meanings attached with human ethics and behaviour, thus conflict can only arise. A basic definition of a ‘market society’ likens it to a social political structure similar to the free market style of capitalism (Adam Smith), whilst also referring to government instituted and or controlled forms of the market, also known as capitalism (27). However, this is still quite broad. A real position on the phrase “market society” comes through its comparison with the phrase “market economy”

“When the market is no longer servant but becomes the master and the value of everything is measured by what people are prepared, or able to pay for it, we have not only a market economy but also a market society….”When the logic of market transactions invades most spheres of social life, everything becomes a commodity and ultimately nothing is worthy of respect” (28)

A market needs a society and vice versa, they need to co-exist, however, in the end, the market feeds off the society, whilst the society is merely facilitated by the market. The market can be manipulated but mostly importantly, it manipulates people.

Climate Refugees:

A report by Essam El Hinnawi in 1985, for the UN’s environment program defines climate refugees as

A category of persons “who have been forced to leave their traditional habitat” because of a marked environmental disruption “that jeopardized their existence and/or seriously affected the quality of their life.” (29)

Neo-liberalism:

- Global management is guided by neo-liberalist ideology

- Value is equal to price

- Value of species to be saved from extinction by what must be paid for their protection

- Cost of pollution by the price paid for emission entitlements, sold by those who pollute less to those who pollute more

- Does not recognize limits to market forces, but only to the efficacy of government action. (30)

Matrix of

Lines of social tension, representing deep fissures in industrial civilization. (31)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Source: UNDP Human Development Report 2005, http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2005/pdf/HDR05_complete.pdf

Figure 3

Source: International Labour Organisation

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/5059106.stm

Source: Myers, N., 1994, “Environmental Refugees; a crisis in the making”, in People & the Planet, 3(4)

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Source: A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, 2005 www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

Footnotes

1. “A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

2. Myers, N. “Environmental Refugees; a crisis in the making”, in People & the Planet, 3(4), 1994.

3. UNDP Human Development Report 2005, http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2005/pdf/HDR05_complete.pdf

4. , S., 1998, “ and its Discontents – Essays on the new mobility of people and money”, The new

5. Morrison, R “Ecological Democracy”, Boston, MA, 1995 p.70

6. Ibid, p.85

7. John Nevile, The Australia Institute, 2000

8. Joshua Skov, Responsibility in the global Age

9. UNDP Human Development Report 2005, p.51

10. Ibid, p.51

11.“A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

12. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 2000

13. Simms A., 2005 “Ecological debt, The Health of the Planet and the Wealth of Nations”, Pluto Press,

14. “A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

15. Taylor, S, “Call to protect environmental refugees: crisis set to grow”, 2003, http://www.neweconomics.org/gen/news_envirorefugees.aspx

16. Myers, N. “Environmental Refugees; a crisis in the making”, in People & the Planet, 3(4), 1994.

17. The Australia Institute, Screw You

18. Consibee M., Simms A., “Environmental Refugees –The case for recognition”, 2003, New Economics Foundation,

19. A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

20. Lester R. Brown, 1992, “Launching the Environmental Revolution, Sate of the world: A worldwatch institute Report on Progress toward a Sustainable Society”,

21. A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

22. A citizens guide to Climate Refugees”, www.foe.org.au/download/fullcitizensguide.pdf

23. Simms A., 2005 “Ecological debt, The Health of the Planet and the Wealth of Nations”, Pluto Press,

24. Morrison, R “Ecological Democracy”,

25. Jean Lambert, Greens MEP 2002

26. www.deh.gov.au/soe/2001/heritage/glossary.html

27. www.wikipedia.com

28. The Australia Institute http://www.tai.org.au/Newsletter_Files/NEwsletters/nl24.pdf#search=’market%society’

29. Consibee M., Simms A., “Environmental Refugees – The case for recognition”, 2003, New Economics Foundation,

30. Morrison, R “Ecological Democracy”,

31. Morrison, R “Ecological Democracy”, Boston, MA, 1995 p.70

2 comments:

very well written article.

suprisingly it seems to be forgotten by most... and not interesting enough for the media.

it makes you think that michael crichton in his fiction "state of fear" is more "realistic" about it all then our daily newspapers, which do not spend much time on the topic at all.

...nice work!

I agree, very well done Sarah!

Sarah was one of my students in a subject called Environmental Design, whose coordinator was Dr Darko Radovic. Her contribution to the class, as you can see from her paper was tremendous.

Rather than designing, this subject aimed to discuss the issues and practices that are more or less conducive to environmentally responsible design. In this case, the topic and question for the semester was: The Market Society and Environmental Sustainability: new urban developments for a sustainable society.

The aim was to dissect and understand the concepts, the overlaying agendas in play and their different degrees of influence when establishing the aims for urban development. How can the agenda for a sustainable society be enabled?

We discussed the impact of the market economy in society, or what it is called "market society", a society whose relationships are mediated by the type of logic that a market economy would encourage, and in which everything becomes a commodity.

As it is always the case, I also learnt a lot through teaching this subject. I was not aware of Tuvalu then and Sarah provided with this tragic an excellent example - a market society that turns its back to those who suffer the consequences of globalisation and our own environmental abuse for the sake of profit.

(by the way, another great paper from this subject was Mark Lam's, also in Studio+Space)

Beatriz C. Maturana

Post a Comment

Please select a profile under "comment as". If you don't have a profile, sign as "anonymous" making sure you write your name in the body of your comment.